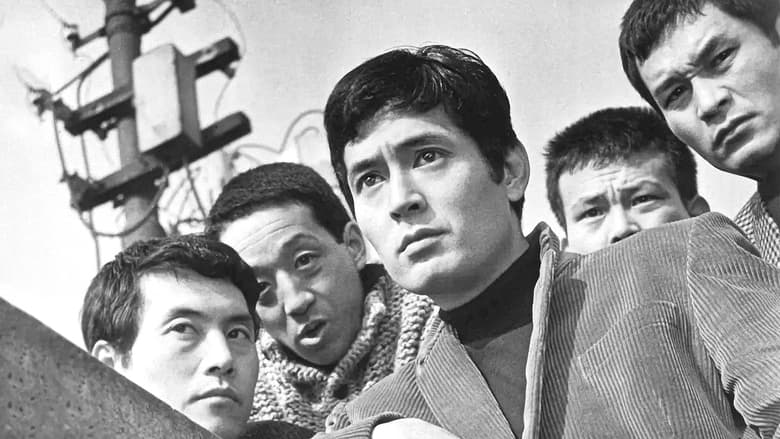

Before leaving prison, Oida uncomfortably enters into an agreement with his cell mate: in exchange for a half-share of 30,000,000 yen, he is to assassinate three strangers given to him on a list. However, upon meeting his first potential victim, Oida has second thoughts. Yet, even as he tries to back out, the body count starts climbing. Oida must now try to alert the people on his list of their impending danger, and find out why they are being targeted in the first place.

Reviews

Fun premise, good actors, bad writing. This film seemed to have potential at the beginning but it quickly devolves into a trite action film. Ultimately it's very boring.

It's an amazing and heartbreaking story.

It’s fine. It's literally the definition of a fine movie. You’ve seen it before, you know every beat and outcome before the characters even do. Only question is how much escapism you’re looking for.

The movie's not perfect, but it sticks the landing of its message. It was engaging - thrilling at times - and I personally thought it was a great time.

Most enjoyable 1966 b/w noir thriller from Japan. Super jazzy soundtrack, great cinematography and solid performances all round, including that of a very young little girl. A deal done in jail as one of them is released just over a week before the other precipitates a tough and non-stop action movie with great location shooting evoking a fantastic picture of late sixties, back street Japan. I thought I had lost the drift fairly early on but it transpired it was intentional, so all was well and particularly for a Japanese film of this period, it is remarkably simple to follow, despite all the usual complications and cases of double cross. Maybe. Oh and as usual you won't anticipate the ending.

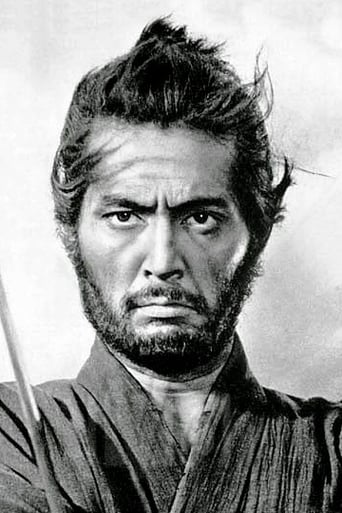

This Shochiku-Haiyuza coproduction works as a transitional step in Hideo Gosha's filmography. On one hand carrying over the social- minded consciousness of his first two films, while paving the way for the dark, pulpy aesthetics of his following three films, the conceived with regards to a serialized character Tange Sazen and the Secret of the Urn and the two Samurai Wolf films, while maintaining the elaborate plotting and heavy emphasis on intense stylization that characterizes all of his films.Oida, played by stalwart actor, samurai icon and regular Gosha collaborater Tatsuya Nakadai, is let in on the plot of a smalltime crook while doing time in prison for killing a man and his child in a traffic accident. Trying to pick the pieces of his life as it came crashing down after the accident, he agrees to track down and murder three men. Something he doesn't seem very intent on doing, preferring instead to find out by the three men the plot they were all in together that sent their accomplice in prison. The only problem is a Hong Kongese drug dealer and his boxer henchman murdering them before he has any chance to find out more.Gosha takes us for a tour through the seedy, rundown, sleazy life of postwar Japan, but whereas other Japanese directors sampled that selfsame seemy underbelly for colour, he seems to have a point to make. And while the plot and dialogues are second grade pulp filler, the kind of which you'd sooner find in a cheap viper page-turner, his visual calligraphy has something to communicate. Notice for example how all murders take place in shabby industrial structures. Old docks, a large water purifiying station, a waste dump with decrepit cars, an electric station. The Japanese Dream wasting away in a monochromatic postwar hell of decrepit back-alleys, cheap cabarets and dilapidated buildings, an ideal place for old dreamers, victims of that dream, to die in.Most important in this interpretation is the way Gosha types the characters soon to be dead. A weary ex-cop who fell in love with the wife of a gangster, a factory worker who never took life in his own hands, a down-and-out ex-champion middle weight boxer, all victims of a society that is as much a victim of itself. As much a parable on Japan's rise and fall before and after WWII as a condemnation of old traditions. And through this carefully constructed topology walks Oida, at first trying to shy away from responsibility (the orphaned daughter of the first victim that follows him around and then becomes attached to him and he to her), then reluctantly embracing it, finally discovering again meaning and purpose in a life that had been devoid of any.As a beautifully photographed, intricately-but-not-very-compellingly plotted noir thriller, Cash Calls Hell is good. Not excellent but enjoyable throughout. It's telling however that the really beautiful moments when Gosha achieves genuine pathos, above and despite genre conventions that call for bloodshed and intrigue, don't concern who stole the money or who's getting whacked by whom but the heartfelt interactions between the little girl and Oida. Simple and evocative, these small moments, not only better flesh out Oida's character, but elevate the movie to a different level altogether.Overall Cash Calls Hell is another fine addition to the Gosha canon. Genre fans will have a ball.

GOHIKI NO SHINSHI bears all the hallmarks of film noir: a labyrinthine plot involving crime and betrayal, gritty urban settings, expressionistic black-and-white camera-work, and a hero seeking redemption for his sins. The film begins with Oida (Tatsuya Nakadai) in prison for killing a man and his daughter in a car accident. He didn't mean to do it, but the fact that he was distracted by an argument with his bar-hostess girlfriend, whom he was about to dump to marry his boss's daughter, increases his sense of guilt and our sense that he might be a selfish, opportunistic man. A few days before he is to be released, Oida attracts the attention of another prisoner, Sengoku, when he risks his life to help capture a knife-wielding inmate. Learning Oida's story, and that he has no life to return to (he lost his job and fiancée because of the accident, and has no family), Sengoku makes him a proposition. The payoff is big; no questions are allowed. He is to assassinate three men for a share of 30 million yen.Oida drifts into accepting the deal but soon has second thoughts. He meets the first man, Motoki, and comes close to pushing him off a dock while he's drunk, but can't quite do it. When he leaves him briefly, Motoki is killed by two mysterious, trench-coated gangsters. Oida tracks down the other two men on his list, not to kill them but to warn them that their lives are in danger. He also becomes the reluctant guardian of Motoki's orphaned daughter, the adorable pigtailed Tomoe. He obsessively tries to uncover the secret behind the strange colliding vendettas: why do both Sengoku and the gangsters want the three men dead, and what happened two years ago at a train station? (We have some idea, having seen a heist, stylishly shot in negative, over the credits). Each of the three men tells a story about how he slipped into crime: one is a former cop who fell in love with a criminal's wife, another a boxer who had his arm broken after he refused to throw a fight. Everyone is sad and desperate, including Sengoku's girlfriend, a bar hostess who says, "We're all prisoners on death row," and the widow of the man Oida killed, whom he meets backstage in a cabaret, still burning with hatred for him.This is not Ozu's Japan. "Seamy underbelly" hardly does justice to the film's settings: grimy docks, industrial warehouses, junkyards, prison yards, deserted amusement parks, alleys, strip clubs and cheap bars where two hostesses have a vicious cat fight in the bathroom. Amid this squalor the elegant, beautiful Nakadai moves like a fallen angel, spellbound by melancholy and remorse. Slowly he comes to life as he finds a purpose in protecting Tomoe, who follows him like a lost duckling, calling him "Oji-san" (uncle). He lets Sengoku think he killed the men as instructed, planning a double-cross of his own. When Tomoe is kidnapped, fate provides him with a chance to redeem himselfbut it won't be easy, since the newly-released Sengoku cares as much about money as Oida cares about his buying back his soul.Hideo Gosha was a master of genre, making a slew of chambara (swordplay) and yakuza (gangster) films. He's principally a stylist, and at times the style overtakes the substance and gets a bit rococo (he loves startling cuts and long-drawn-out fights.) Nakadai said that the director often cared more about the images than the story, but called him an "impassioned" filmmaker. GOHIKI NO SHINSHI is a fairly standard thriller, impeccably entertaining, and the combination of powerful acting and authentic locations give it a special weight. What lingers most is the weary, lyrical evocation of a world full of hurt, where moments of gentleness are rare and precious. The only flaw is a musical score than tends towards cheesy cocktail jazz, nudging some scenes close to sentimentality. And what was it with the harpsichord in 1960s Japanese films? NOTE: GOHIKI NO SHINSHI is a truly untranslatable title: it means "Five Gentlemen," but "hiki" is the counter word used not for people but for small animals: so the five "gentlemen" (presumably Oida, Sengoku and the three targets) are also animals in the urban jungle.(Thank you to my Japanese-speaking friend for explaining this to me.) However, surely a more coherent English title than CASH CALLS HELL could have been concocted.

After viewing a heist (in negative black-and-white) during the opening credits, we find our protagonist, Oida -- Tatsuya Nakadai, excellent as usual -- in prison. Sent there for killing two people in an automobile accident (the result of a split-second lapse in attention), he's now to be released.Having lost everything, he has nowhere and nobody to turn to upon his release, so Oida uncomfortably enters into an agreement with his cell mate: in exchange for a half-share of 30,000,000 yen, he is to assassinate three strangers given to him on a list. Unknown to him, drug dealers, seeking to get back money stolen in the heist years earlier, are after the same three men. Upon meeting his first potential victim, Oida immediately regrets his decision, but, needless to say, the body count starts climbing, and he's drawn irreversibly into the vortex. Complicating matters, Oida is "adopted" as a father-figure by the orphan of the first victim, and then encounters the widow of the man he killed years earlier, backstage in a seedy club.Oida decides he must now try to alert the people on his list of their impending danger, and find out why they are being targeted in the first place.Complete with grotesque characters, questionable alliances, double-crosses, a chance of redemption, and fabulous black-and-white photography, "Cash Calls Hell" is pure noir, and is easily equal to Kurosawa's justly praised "The Bad Sleep Well" and "High and Low." While director Hideo Gosha obviously made some fine samurai movies during his career, I can't help thinking the world would be a richer place if he'd made more films like this overlooked gem. No fan of film noir, Hideo Gosha or Tatsuya Nakadai should miss "Cash Calls Hell."

Top Streaming Movies