Down-on-his-luck veteran Tsugumo Hanshirō enters the courtyard of the prosperous House of Iyi. Unemployed, and with no family, he hopes to find a place to commit seppuku—and a worthy second to deliver the coup de grâce in his suicide ritual. The senior counselor for the Iyi clan questions the ronin’s resolve and integrity, suspecting Hanshirō of seeking charity rather than an honorable end. What follows is a pair of interlocking stories which lay bare the difference between honor and respect, and promises to examine the legendary foundations of the Samurai code.

Similar titles

You May Also Like

Reviews

Touches You

The film's masterful storytelling did its job. The message was clear. No need to overdo.

The story, direction, characters, and writing/dialogue is akin to taking a tranquilizer shot to the neck, but everything else was so well done.

Worth seeing just to witness how winsome it is.

Social criticism on the samurai culture during the Tokugawa Government of the 1600s , when the Shogunate were disbanding samurai clans and many were left wandering in poverty. The beginning of the merchant era , during a time of peace , and samurai were no longer necessary for society. This film questions samurai traditions and the integrity behind them: the rise of lawlessness among wandering samurai (taking advantage of dojo's kindness during peace era), not having a proper sword for seppuku, allowing or not a day or two for reconciliation with one's loved ones before seppuku, biting off one's tongue, the rise pf merchants impoverishing the people, the importance of top-knots, and the meaning of God in Shogun armor. This movie takes stab at all samurai practice with a moral compass between right and wrong. Not matter what social faction we belong to , in the end we are all human which transgresses all

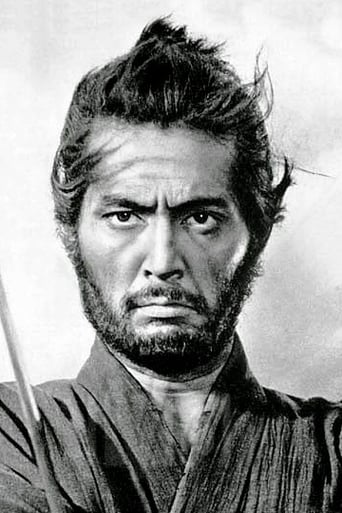

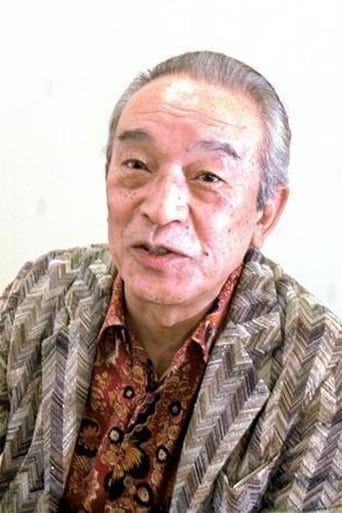

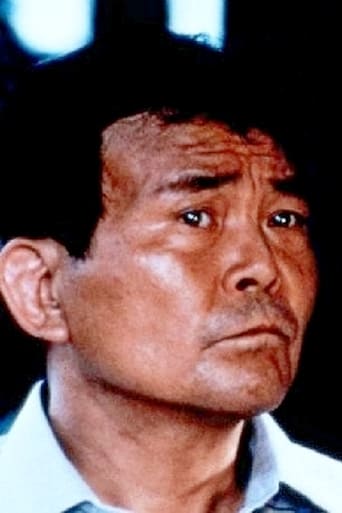

The first shot of Harakiri is an imposing suit of samurai armour, seated on a bench amongst cinematic coils of smoke in the air. I say seating, because despite its hollowness, it's posture is imposingly life-like, almost as if at the call of war it would come to life and march off to battle. This must be how the Ii clan see this glorious suit of armour; even in peacetime it is more than just a tool for means of driving back enemies, but a symbol for honour, strength, loyalty and absolute morality. Of course as they prosper, the peacetime has released many ronin, now master-less and without a trade or living, into the wild wandering. This is really a film for a repeat watch. On first impression, Motome's pleas seem a little self-fulfilling, because why would a samurai committed to seppuku want a two day respite if they have renounced everything and are ready to die? His actual act of seppuku too, is extremely hard to watch - Kobayashi doesn't need to show actually graphic penetration because Ishihama's agony is so anguishing to witness. And yet, there is a hint of comeuppance, because it seems phony that a samurai would carry around a fake, bamboo version of his livelihood. On a second watch, these scenes are filled with such a tragic desperation once we know the back-story. The blunt, ironic cruelty of the bamboo strikes becomes heartbreaking because he has already sold his real blades for his family - what is a samurai without his blade? We know without a doubt he would return in two days this time. Doubly so, Hanshiro weeps because he has kept his own blade, foolishly holding onto a past relic much like the witnesses around him do so. Kobayashi has maintained such a steady, tense rhythm throughout the two hours and 13 minutes. Not once is there a line of misplaced dialogue, or a glance that was not filled with the appropriate amount of venom. We see one 'extortion' attempt, and then another from Hanshiro, so of course we await some sort of twist or connection. There is no sense of contrivance when he delays the act, no sense of artificial direction behind these characters. Tatsuya Nakadai is effortless. He has the knack for transforming so seamlessly into his character and becoming every ounce of them - here it is in his blank, almost traumatised expression as he narrates; it could not be more immediately obvious that this is a man who has lost everything. And then there is the little remaining spark underneath that drives this tale of revenge (his cackles as he bemusedly wonders on the fate of three men he has already taken care of), although it seems more vital to expose the Ii clan for the facade that they uphold. The framing device of the narration of the guest book is what seals it. It simultaneously empowers and suppresses the events of the film; even as we witness the despair of Saito, having his pretense so viciously and comprehensively demolished, he quickly rewrites the history books because he has that power (there's a cruel irony to the way he orders the forced seppuku of the three disgraced warriors - the noble ritual being marred). That stirring, dramatic duel in the windswept plains, gone. That desperate, climatic battle, where we might conventionally expect a one-man massacre and a little poetic justice, gone. And even as he attempts to go out on his own terms, Hanshiro is shot by a modernised death-dealer. It recalls Kurosawa's Yojimbo, in which it was actually Nakadai who wielded the gun and brought forth the end of the age of samurai. But here, it becomes a more potent, universally symbolic end. This cruel world does not bend to sentiment. Appearances must be upheld, even sometimes in the face of moral transgression. Hanshiro smashes the suit of armour, but it is gleaming and whole again soon. But it is of course a hollow ideal. All the honour in the world could not materialise a decent man to fill its shoes.

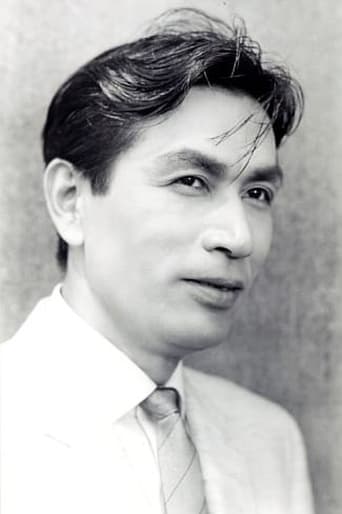

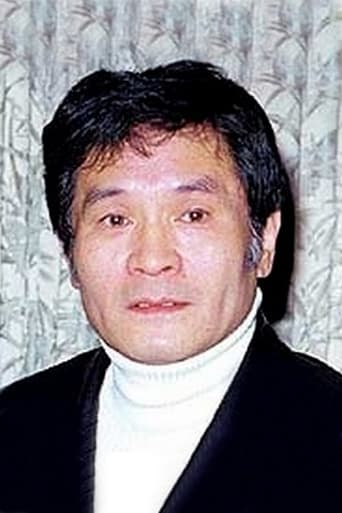

American ethos has always had a soft-spot for the conscientious objector. We're a nation of fervent individualists and everything from the writings of Mark Twain to the film 12 Angry Men (1957) codifies that idea. The power of an individual against a torrent of common corruption and blind group-think is almost fetishized, especially in contemporary society. The Japanese, generally speaking, don't have such a provocative streak of individualism embedded in their culture. So it's interesting that one of the most eloquent and austerely beautiful films on the subject should come from the land of the rising sun. Harakiri is a repudiation of the collective values of Japan that, on its best days unites a population in tragedy and at its worst marches a people towards war.Hanshiro Tsugumo (Nakadai) is an aging and embittered samurai whose feudal lord has died in battle along with most of his men. In order to reclaim his honor, according to the bushido code, Tsugumo must disembowel himself in a ritual suicide known as seppuku. To do this he arrives at the feet of Saito Kageyu (Mikuni) and asks members of the Iyi daimyo to help him do the ceremony correctly. Kageyu is hesitant as only a few days ago a similar request was made by another ronin who had no intention of committing seppuku but was looking to extort the clan for money. After Kageyu retells the man's tale, which culminates in the ronin dying by the blade of a bamboo sword, Tsugumo insists his intentions are to die with honor. Yet as the pavilion where the deed is to be done is setup, questions remain. What is Tsugumo's connection to the earlier ronin? Why did he pick the courtyard of the Iyi clan out of all others? Finally does he really intent to reclaim his honor, or is there something else going on?Told in a dizzying array of flashbacks and flash-forwards, Harakiri is not a leisurely movie to watch while folding laundry. It demands the attention of the viewer and weaves a complex tale of Hanshiro Tsugumo's home life after the fall of his clan. He's stricken with the most dire poverty, contemplating his daughter's (Iwashita) sale as a concubine and working menial jobs just to get by. His daughter, son-in-law Motome (Ishihama) and infant grandson Kingo are his only solace from a life of dishonor. Their fates become intimately intertwined with Tsugumo and the Iyi clan in unexpected ways and paying close attention to the plot pays off stunningly in the end.In his own quiet and ultimately unsettling way director Masaki Kobayashi strips away the nobility and romanticism commonly associated with feudal Japan. While doing so he implicates the modern audience (at the time the Japanese public circa 1962) in tolerating authoritarianism under the guise of honor. Harakiri recalls and parallels the days of Japanese imperialism and uses a single individual as a means to take apart the misplaced hubris of anyone still beholden to the old guard. Kobayashi himself was drafted in the army during WWII but repeatedly refused promotion beyond that of a private; his own way of fighting corruption, hypocrisy and evil.The film comes to a conclusion so damning and memorable that I dare not ruin the satisfaction of watching it for the first time. Harakiri is an absolute treasure featuring a star turn by Nakadai who first made an indelible mark on Japanese screens in Kobayashi's The Human Condition Trilogy (1959-1961). Here, while playing a character much older than himself, he still has a certain inner- turmoil that channels James Dean with a strong baritone. Finally there's Kobayashi's masterful direction which watches pensively and almost perversely as the jigsaw pieces fall in place.

"Who can know the depths of another man's heart?" Hanshuro TsugumoApart from its sheer story-telling gravitas and technical splendour, Kobayashi's Hara-kiri is especially lauded for its plea to look closer, to examine a little more deeply the troubles of those not as fortunate as us. When I watched it for the first time, I was blown away by the arresting wallop of this tension-saturated story's narration , and it was on the second viewing years later that I registered with more delicate acuity, its eloquent entreaty for a more compassionate look at the surface issues of our brethren. Particularly in Japan, the practice of bowing to the larger system and the concept of "honour" being maintained at all costs, looms especially large but of what use is honour if it makes us lose everything dear to us? Hara-kiri takes on the form of a formidable Samurai drama and builds this visceral sentiment with inexorable power, the vise of its narrative swirling and tightening until the physical carnage at the end isn't necessary - the foes have already been annihilated with gentle words. World-class cinematography and flawlessly strong acting further power this monochrome scorcher.Pic opens with a wide-angle black-'n'-white canvas , the neatness and sparse beauty of which is the trademark of director Masaki Kobayashi. Notice how clean these compositions are, whether it is the large ground ouside a chieftan's house, the inner courtyard with its settled pebbles and carefully coiffed platforms for sitting, or even a poor man's wooden house bereft of much conveniences and yet almost spacious in its tidy gestalt. The framing is immaculate when Motome Chijiwa (Akira Ishihama) - a young Samurai struggling for survival - sits with folded knee - in a martial lord's house in front of a tough-jawed warrior who listens to his case. It is 1630 in the Edo region of Japan - peace has been declared in the land but it has devolved into internal war for the highly trained swordsmen called Samurai - they find no employment now, jobs are scarce with workers pouring into any open job-site and Motome is pushed away by a supervisor who cries out that the supervisor will be punished if authorities find out that the formal warrior class is being employed for menial jobs. Motome reports to the House of Li , as other Samurai have done before him, that this utter penury is so dishonourable that he would rather commit Seppuku by disemboweling himself with his own sword in this martial house's courtyard as a final act of honour. The House of Li, manned by fierce-looking superiors, is fed up with this pattern of supposedly suicidal Samurais - they see that many such applicants are willing to accept some money and go away without killing themseles as they initially declared to do. At this stage, Kobayashi racks up the sense of foreboding , panic and icy fear with such elan that the ensuing twenty minutes ranks as one of the most implacable turn of events in black-'n'-white cinema. A few days later, a middle-aged man named Hanshuro Tsugomo (Tatsuya Nakadai), bearded and rather emaciated-looking, shows up at the House of Li with a similar request. He is told the story of Motome Chijiwa as a warning - but Tsugumo, with a wry expression that is beyond gallows humour, calmly states that he will indubitably execute as promised. As great as the previous tightly coiled sequence was, this succeding chapter matches it with its slow burn and unbearable tension which Tsugumo stretches far past breaking point with a story he unspools. Counsellor Saito (Rentaro Mikuni) , heading the house in the absence of the martial lord, is , to put it presisely - driven nuts - by this seemingly interminable narration by the grave-faced Tsugumo but I never got tired of hearing it as the latter lays one dialogue upon another like one revelatory card against the next one till the stakes indicate not just one death but many more. Saito , his strings plucked like a hen stripped to the bone , retreats to the house unable to take more.In other jidaigeki (period-films) like Kurosawa's great "Throne of Blood", the performances though solid do not evoke my specific praise but in Harakiri ,the thespian finesse is on prime display - this could very well have been a starkly lit theater-drama. One can almost feel the cool breeze of happiness coursing through Motome's smiling immensely relieved face after the stifling humidity of despair, alas later , stomach-churning panic sets in to seize his mien. Tsugumo's nominally amused ,mostly dead-serious physiognomy never ever raises its voice but the prosody of his message undulates with the timeless meaning of great scripture. And then there's Saito , more c**t than counsellor, who's so drunk with power and delusions of tough wisdom that his sobriety is nullified by incurable hauteur.I was vastly disappointed by the fight at the end on my first viewing - having brought me to the very peak of expectation, Harakiri's climactic sword-fight seemed not even close to the supremely choreographed ahead-of-its-time bristling magnificence of Daibosatsu toge's finisher. But then as Saito himself says , Tsugumo is a "half-starved" Samurai who's already been through many hells so it is perhaps unfair to expect him to again fight like Japan's greatest champion. The denouement is a sobering indictment of the way history often operates, and the film eventually reclaims its spell-binding emotional and technical territory . To watch Hara-kiri , then , is to acknowledge that even in 1962 when so much of the rest of the world was learning the ropes of top-tier movies, Japan was already capable of engineering peerless cinema.

Top Streaming Movies